Wood vs. Steel: The Exact Calculation of Embodied Carbon Reduction in Mass Timber Structures

A data-driven breakdown of how much carbon mass timber truly saves compared to steel and concrete, backed by real LCAs from award-winning buildings.

The built environment is undergoing a structural revolution—not driven by new alloys or futuristic composites, but by a material humanity has used for thousands of years. Wood, re-engineered through modern mass timber technology, is emerging as one of the most powerful tools for decarbonizing construction. But claims alone are not enough. In an era defined by climate accountability, we need precise, verifiable numbers, not optimistic assumptions.

This article unpacks the true embodied carbon difference between wood and steel through two of the most rigorously studied mass timber buildings in North America.

What Embodied Carbon Actually Measures

Embodied carbon represents the total greenhouse gas emissions generated by creating a building's materials—from extraction and milling to transportation and installation. With operational emissions trending downward due to clean energy grids, embodied carbon now represents:

- up to 50% of a building’s lifetime emissions, and

- nearly 100% of emissions for net-zero operational buildings.

Steel and concrete dominate global emissions because their production is inherently carbon intensive. Cement releases roughly 0.9 tons of CO₂ per ton produced, while primary steel manufacturing can exceed 2.5 tons of CO₂ per ton—a figure driven by coal-based blast furnaces.

Wood behaves differently. It stores carbon absorbed during growth. When responsibly harvested and used in buildings with long service lives, that carbon stays locked away for decades.

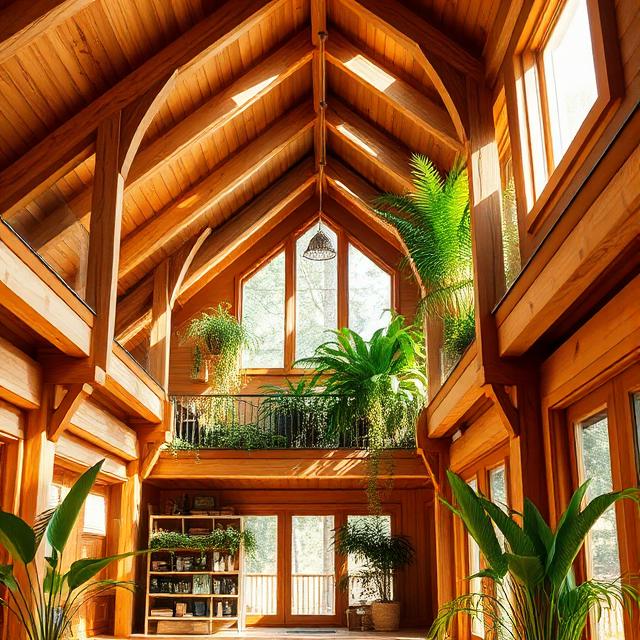

Case Study: Barry Mills Hall (Bowdoin College, Maine)

Bowdoin College’s Barry Mills Hall is one of the clearest demonstrations of mass timber’s carbon advantage. Designed by Leers Weinzapfel Associates, the building employs glulam beams and CLT panels for its full structural system.

A full life-cycle assessment (LCA), verified under ISO 14044 and EN 15978, concluded:

- 75–80% reduction in embodied carbon compared to a steel-frame equivalent.

- The structural system alone reduced emissions by ~55%.

- The wood used in the building stored ~430 metric tons of CO₂e, pushing the net carbon balance into negative territory.

This isn’t a symbolic gesture. It is a measurable removal of atmospheric carbon equivalent to taking nearly 100 cars off the road for an entire year. The building becomes a long-term carbon vault.

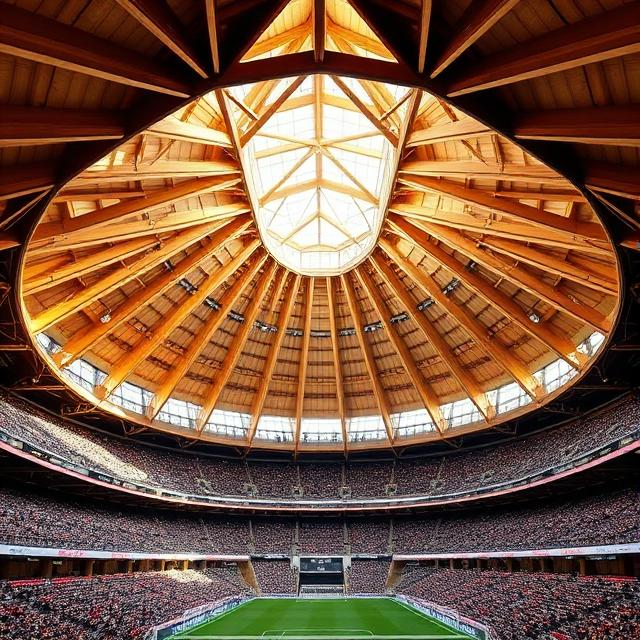

Case Study: Kaiser Borsari Hall (Western Washington University)

Kaiser Borsari Hall, designed by Mithun and DCI Engineers, is a landmark moment for timber in high-performance, technically demanding environments—specifically STEM education and research.

Its hybrid system includes CLT floors and walls supported by glulam framing, with minimal concrete used only where structurally necessary.

Peer-reviewed LCA results show:

- a 60% reduction in global warming potential (GWP) compared to a conventional concrete-and-steel baseline,

- a 30% reduction in construction waste due to off-site fabrication,

- a four-month shorter construction schedule, reducing on-site fuel consumption,

- 620 metric tons of biogenic carbon stored within the structure,

- and ~380 metric tons of avoided CO₂e relative to the conventional alternative.

Combined, this results in a net carbon benefit of 1,000 metric tons—equivalent to preserving 250 acres of U.S. forest for an entire year.

The Bigger Pattern Across Industry Benchmarks

Across dozens of LCAs published in North America and Europe, mass timber consistently demonstrates:

- Embodied carbon reductions of 60–85%, depending on system type.

- The ability to store more carbon than it emits when biogenic storage is included.

- Dramatically lower impacts in categories such as acidification, eutrophication, and ozone depletion.

- Fewer emissions from construction logistics due to lighter weight and faster installation.

To translate this into real-world scale: a mid-rise mass timber office building (around 8–12 stories) typically avoids 2,000 to 3,000 metric tons of CO₂e compared to steel.

That is comparable to:

- the electricity usage of 350 U.S. homes over a year, or

- avoiding 700 transatlantic round-trip flights.

Common Counterarguments and the Real Data

1. Forest Impact

Both case studies used wood certified by FSC or SFI, with harvest rates below regrowth rates. U.S. and Canadian forests have grown in net volume over the past 30 years, even as timber demand increased.

2. End-of-Life Scenarios

Even in pessimistic scenarios—such as disposal in landfills—timber retains a net carbon advantage over a 100-year timeline. With advancing reuse pathways (CLT deconstruction, engineered wood recycling, biochar), the gap widens even further.

The Bottom Line

The precise calculations from Barry Mills Hall, Kaiser Borsari Hall, and dozens of other LCAs point to one conclusion:

Choosing wood over steel is not a stylistic preference. It is a mathematically quantifiable climate strategy.

When the structure of a building can remove or avoid hundreds—even thousands—of tons of CO₂e, the conversation shifts from sustainability branding to engineering fact.

Wood’s advantage is not based on optimism or marketing.

It is based on physics, biology, and verifiable arithmetic.

In a world where climate deadlines are tightening, precision is not optional—

it is the new standard of excellence.